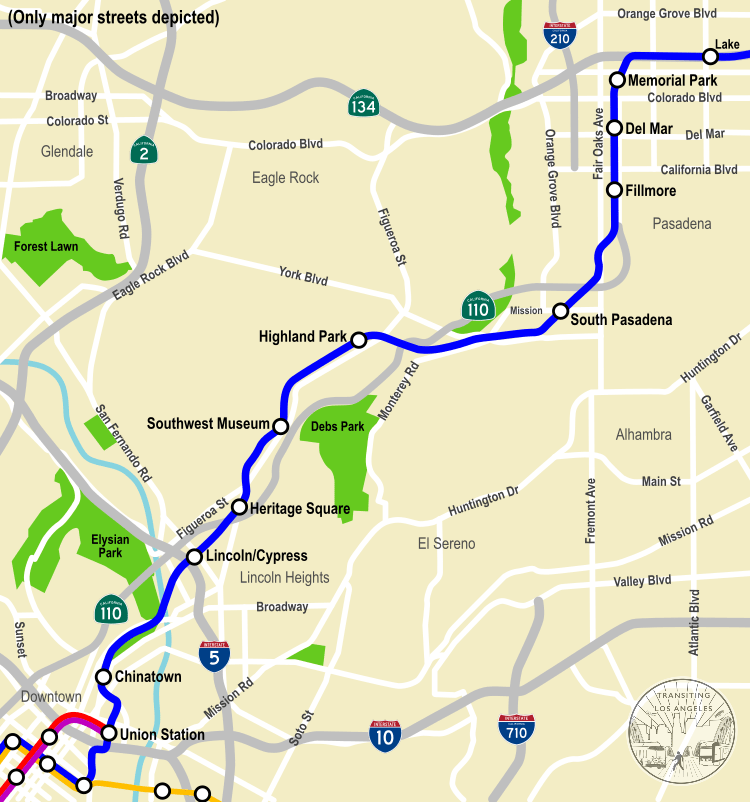

In the 1990s, when planning began on a project to turn an old railroad through the San Gabriel Valley into a light rail line, the project was called “the Pasadena Blue Line,” and envisioned as an extension of the then-brand new Blue Line to Long Beach, connected to the old railroad via a subway tunnel through Downtown L.A. But funding problems and widespread anti-subway sentiment in L.A. at the time prevented the tunnel from being built, so it was constructed as a separate line starting at Union Station, necessitating a different name: the Gold Line. The idea of a single Blue Line running from Long Beach all the way to Pasadena was finally realized with the completion of the Regional Connector in 2023, when it was officially redubbed the A Line.

The section of the line between Downtown L.A. and Pasadena is the most scenic in the whole Metro Rail system, and one of the prettiest of any light rail line in the country. It’s also very historic, following a rail line dating back to the 1880s that proved the be one of the most consequential in the city’s history. This is a case where the journey can be as much of an attraction as the destination.

Starting at Union Station (see our guide to its attractions and history here), the A Line climbs steeply out of the station’s railyard, shared with massive, rumbling Metrolink and Amtrak trains. You might even see a historic train car parked on the “garden track” spur beneath the A Line as it climbs out of the station.

As the train turns to the west, you’re treated to a great view of the downtown skyline with City Hall front and center. To the north, you also get a good view of the hills of Northeast L.A. and the San Gabriel Mountains beyond, provided the weather is good. On particularly clear days in the wintertime, you can even see all the way out to Mount Baldy’s frequently snowcapped peak.

The A Line crosses over a few blocks before stopping on the edge of Chinatown (which we explored in this guide) at one of Metro’s more architecturally interesting stations, with a roof styled after a Chinese pagoda and some cool public art. Past Chinatown station, the train passes by the expansive lawns of Los Angeles State Historic Park (which we cover here), site of the first major train station and railyard in the city, when the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in 1876, thus linking Los Angeles to the rest of the nation by rail for the first time. But the site has history tracing back to the origins of Los Angeles, when the Zanja Madre (“mother ditch”) was built through here to deliver water from the Los Angeles River into the Pueblo (today’s Olvera Street). The path of the Zanja Madre took it along the bottom of the slope next to the train tracks; keep your eyes peeled and you’ll see an excavated part of it, constructed of brick and situated under a retaining wall on the other side of the train tracks from the park.

Past the park, the A Line crosses over the L.A. River, where it passes a number of points of interest. On your right is the complex of Metabolic Studio, an art studio which occupies properties on both sides of the river. Metabolic played a big role in the creation of the park and continues to remain active in the effort to revitalize the L.A. River. At night, you can spot their red neon “CONCRETE IS FLUID” sign from the train.

On your left, wedged between the river and the steep slope that leads up to Elysian Park, is a Metro railyard where trains are stored and maintained. In fact, sometimes Metro employees disembark here at a special platform built on the bridge, so don’t be surprised if the train comes to a stop while crossing over. A nifty little historical artifact remains on the railyard, best viewed from the train if you’re heading towards downtown: on the retaining wall behind the shed closest to the bridge, there’s the faint remnants of a painted billboard for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In the right light, you can just make out the words “Trains Daily to San Francisco.”

The other historic landmark you can see from the train is the hulking remains of Lincoln Heights Jail, which sits on the other side of the river across from the railyard. Built in the 1920s, it served as the central prison for LAPD until being decommissioned in the 1960s, and in its time gained a rather notorious reputation. Since its closing, it has often been used for film shoots, particularly for horror or period films or music videos.

From the L.A. River on, the A Line follows the route of the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley Railroad, built in 1885 to create a rail link between L.A. and Pasadena. The railroad massively boosted land sales in the San Gabriel Valley and quickened the development of the towns along its route. East of Pasadena, citrus groves and vineyards flourished with the new access to markets.

Just a couple years after being built, the line was bought out by the Santa Fe Railroad, which until that point had been bitterly blocked by the Southern Pacific from entering L.A. and breaking their monopoly over transportation into the region. The sudden competition between the railroads led to a bonanza for Southern California, bringing in tons of people and massive economic growth.

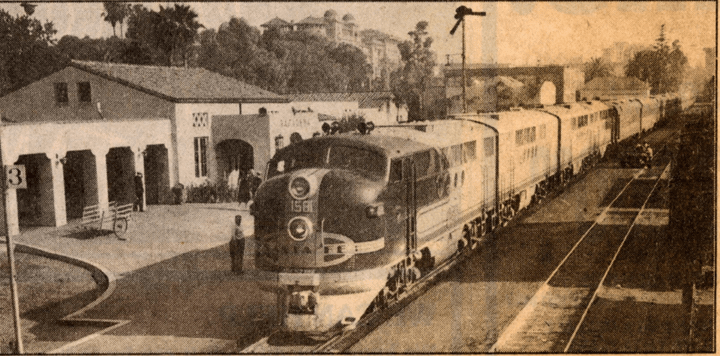

For decades afterwards, the San Gabriel Valley railroad served as part of the Santa Fe’s main line, used for its famed passenger trains between Chicago and Los Angeles, including the popular El Capitan and the iconic Super Chief, precursors to Amtrak’s Southwest Chief, which also used the San Gabriel Valley line until relocating to its current routing through Fullerton in 1994.

After crossing the river and over the 5, the next stop is Lincoln/Cypress, located on the far northern edge of Lincoln Heights. From here, you can walk or take Metro bus #296 to the L.A. River bike trail; see our guide about that here. The train then passes through a mostly industrial area of warehouses and utilitarian functions, including a large junkyard right before passing over the Arroyo Seco and the 110. Keep your eyes peeled as you pass the junkyard: you might just spot their UFO prop that’s been sitting against the back wall of the yard, rusting away for years now.

The A Line makes a couple of quick stops at Heritage Square and Southwest Museum as it climbs through the narrow pass into Northeast L.A. Lots of flowers grow along the tracks here, with lush vines of purple morning glories covering the walls along Heritage Square station and bushes of pink bougainvillea overtopping the walls leading up to Southwest Museum station. Both stations are fairly quiet, serving as neighborhood stops for the tranquil communities along the route.

The Southwest Museum station is particularly calm and pleasant, with some whimsical public art and a lot of nearby attractions. The tower of the former Southwest Museum itself looms on the hillside above the tracks. Sadly, the museum is closed, but we try to keep its memory alive. The eclectic house of the museum’s founder is a fairly short walk away, while just across the street from the platform is a public staircase leading into the exceptionally pleasant neighborhood of Mount Washington. From the platform, you can also look across the valley at the steep hillsides of Debs Park, Northeast L.A.’s version of Griffith Park and full of its own treasures, also within walking distance of the station.

As the train curves around the steep slope holding up the Southwest Museum, it crosses over a small tree-lined wash before entering Highland Park. This stretch of track is unique for being in the median of an otherwise quiet residential street, passing houses and apartment buildings, and it’s hard to conceive that at one point locomotives and freight trains were using these tracks. A handful of murals are visible from the train; on your right you’ll see the complex of Avenue 50 Studio as soon as you enter the neighborhood; just past Ave 56, a colorful “Northeast LA” mural adorns a garage on your left. Further on past Highland Park station, a beautiful Aztec-inspired mural graces a wall facing Ave 61.

The station itself is just a block from a bustling section of Figueroa Street in the heart of the neighborhood. Right next to the station, a small farmers market takes place every Tuesday afternoon. Highland Park is in the midst of a wave of gentrification which has resulted in a lot of long-standing businesses closing their doors, so sometimes it’s hard to know what to recommend when your favorite place might shut down next year. Our personal recommendations would be to check out Delicias Bakery, a family-run Mexican bakery on the corner of Fig and Ave 56, housed in the same building as the Lodge Room, a former Masonic lodge-turned-music venue. A couple blocks further down, in the strip mall facing Fig and Ave 54, are the incredible queso tacos of Villa’s Tacos. And just around the corner from the train station, on Fig between Aves 56 and 57, is Highland Park Bowl, which is definitely pricey and caters more to the hipster crowd, but is still worth checking out for its history and vintage decor.

If you want to enjoy a quieter side of the neighborhood, a few blocks down Ave 57 on the other side of Figueroa is Tierra de la Culebra Park, a community art park tucked onto a hillside above the street. It’s a real local gem, with lush terraces filled with gardens, seating areas, and artwork created and maintained by local school children.

As it leaves Highland Park, the A Line crosses over the Santa Fe Arroyo Seco Railroad Bridge, crossing the 110 and the Arroyo Seco on its way north. This bridge is the tallest, longest, and oldest railroad bridge in L.A., dating back to 1896 and spanning over 700 feet across the canyon. As you cross over, you not only get a great view over the neighborhood and highway below, but a sweeping vista of the mountains to the north.

After cutting across a hillside, the train slices through some quiet neighborhoods before making its next stop at South Pasadena. This is one of the most charming communities in the entire region, with the station situated right in the middle of a very walkable district of historic buildings, shops, and cafes, which we explore in more detail here. A popular farmer’s market takes place right next to the station every Thursday evening, outside the town’s small historical society museum which holds exhibits on the town’s railroad history. In the plaza next to the station entrance is a statue of a man striding across a set of granite stones, which according to the attached plaque were once foundational supports for the original wooden trestle railroad bridge that crossed the Arroyo Seco between Highland Park and South Pasadena.

One attraction that’s visible from the train is right across the street from the South Pasadena station, on your left right after the train crosses the intersection. The wooden, pale blue house on the corner is the Century House, one of the oldest buildings in town. But it’s better known as the Michael Myers House for its use in the horror film classic Halloween. Keep your eye out as the train passes the house, you might spot the prop skeleton that normally lounges on the roof in the backyard.

After crossing over the 110 again, the train enters a tree-lined trench that carries the line through the hilly neighborhoods separating South Pasadena and Pasadena. On your right, a large semi-permanent tent serves as the building site for South Pasadena’s annual Rose Parade float. Just after that, the train passes under a graceful pedestrian bridge designed by Greene & Greene, the architecture firm famed for its Craftsman houses and mansions. The A Line continues to follow the trench, curving around Raymond Hill and crossing under Fair Oaks Avenue before passing through Pasadena’s power plant and entering Pasadena proper.

The section of track through Pasadena once ran parallel to what has become perhaps the city’s most mythologized piece of infrastructure. For a brief time in the year 1900, Pasadena was home to an elevated bicycle toll road called the California Cycleway.

Built to capitalize on the bicycle craze of the 1880s and ’90s, the Cycleway was the brainchild of local businessman and politician Horace Dobbins. Constructed of wooden planks and elevated above the streets of Pasadena, the Cycleway ran from Hotel Green (next to what is now Del Mar station) at its northern end along what is now Edmondson Alley, just a block west of the train tracks.

Dobbins’ plan was for it to go all the way down along the Arroyo Seco to Downtown Los Angeles, which has led a lot of historical accounts of the Cycleway to erroneously claim that it did. Instead, it only made it as far south as Raymond Hill, on the southern edge of Pasadena. The hill was the site of the famed Raymond Hotel, but as of 1900 the hotel was in the process of being rebuilt from a fire. This meant the Cycleway was of extremely limited utility, and financial difficulties caused it to close within a year of its opening. No remnants of it have survived. Today, the Cycleway lives on only as a glorious dream to L.A.’s cyclists, mythologized to the point that it has taken on a symbolic significance in death far above what it achieved in life.

Historical photographs courtesy of the Pasadena Museum of History; source 1 and 2. If you’re interested in more details on the California Cycleway, I highly recommend this great piece on it by Eric Brightwell.

The A Line crosses a mostly industrial section of Pasadena, filled mostly with warehouses, office buildings, and big box stores. The train makes a quick stop at Fillmore, in a commercial area of town just off Arroyo Parkway. Within walking distance of the station is the original location of Trader Joe’s and the Pasadena location of the wildly popular hot chicken shop Howlin’ Rays, which sports an “Adohr Milk Farms” neon sign that dates back to when the building was a dairy in the 1920s.

The next stop is Del Mar, which is surrounded by a newer housing development that envelopes the platform, with covered passageways leading out to Arroyo Parkway and Del Mar Blvd. A fountain lines the walkway out to Arroyo Parkway while a tall, industrial-looking tower (actually a piece of public art) covers the stairwell leading down to the underground parking garage. But the true jewel of this station is the small Mission-style building on the west side of the complex, which served as Pasadena’s train depot from its construction in the 1930s all the way until the termination of intercity rail service to Pasadena in the 1990s. Here, many Hollywood celebrities of the 1940s who took the Santa Fe Railroad’s famed passenger trains would disembark to avoid the crowds at Union Station.

Past the old depot and across the street is Pasadena Central Park, a fairly pleasant public park with lush lawns and plenty of shady trees. At the north end of the park is the stunning Castle Green, built in the 1890s in a mix of Mediterranean and Victorian styles. Today, it’s a fancy apartment building, but when it was built it was part of Hotel Green, a prestigious railroad hotel built to take advantage of its location next to the train station.

After Del Mar, the A Line dives into a tunnel, reemerging to stop at the semi-underground Memorial Park station, situated under the eponymous city park at the edge of Old Pasadena. From the station entrance, you can literally look up the street and see Pasadena City Hall, with its ornate Spanish-style domed tower. Walking the other direction will take you into the historic district of Old Pasadena, with its many shops and restaurants.

From here, the A Line takes a sharp turn east, running parallel to the San Gabriel Mountains. Unfortunately, despite some mountain views, the scenery isn’t much good given that the train runs in the median of the 210 freeway for several miles, and then through some very industrial areas. It’s not until the train almost reaches Azusa, where it comes the closest to the foothills, that the scenery improves. But that’s a trip for another day.

10 thoughts on “Transiting the Pasadena Blue Line”