Los Angeles has a castle. A great, gleaming castle atop a hill that overlooks the city, much like those in Prague, Edinburgh, or Lisbon. Its walls are made of stone that was imported from far away. And like those other castles, it was built in the name of a wealthy ruler, and stands as a lasting testament to the power and prestige of his name.

The main difference is that our castle wasn’t built as a palace or a fortress, but as an art museum.

The outgrowth of J. Paul Getty’s massive collection of European art (which itself was an outgrowth of Getty’s insane oil fortune), the Getty Center is a palatial complex of modern buildings sitting atop a ridge overlooking West L.A. And it offers arguably one of the most unique museum-going experiences in the country, with dazzling architecture, sweeping views, and a lush garden. This is art Disneyland, down to having to take a tram to get to the front gate.

In the summertime, a visit to the Getty is the perfect respite from the inland heat, with its air conditioned galleries and cool sea breezes sweeping up the hills.

It is important not to confuse the Center with the Getty Villa, the original location of the art museum, located on J. Paul Getty’s Pacific Palisades estate. The Villa contains the Getty’s collection of Ancient Greek and Roman artwork, while the Getty Center covers European art from the Middle Ages to Impressionism, as well as rotating exhibitions that often cover more modern artwork and works from the Getty’s famed photographic archive.

The Getty Center is also much easier to reach by public transit, with a bus line dropping you off at the front entrance. Metro route 761 runs between West L.A. and the San Fernando Valley through the Sepulveda Pass, starting at the Metro E Line station at Expo/Sepulveda and continuing up through Westwood and pass UCLA before entering the pass and making a stop at the Getty. On the Valley side, it continues up through Sherman Oaks and along Van Nuys Blvd and San Fernando Road all the way up to Sylmar. It runs every 15 minutes on weekdays and every half-hour on the weekend. Late night service through the Sepulveda Pass is handled by Metro route 233, which covers the same route as the 761 down to the Expo/Sepulveda station after about 8:30pm, though this will only be relevant to a Getty Center visit if you stay until closing time on Saturday (see below).

During the summer, the Getty is open Tuesday through Sunday (closed on Mondays), 10am-6:30pm, with one exception: on Saturdays, the museum is open until 9pm, which is a wonderful opportunity to take in the sunsets overlooking the city. The rest of the year, the Getty closes an hour earlier, so Tuesday-Sunday 10am-5:30pm, Saturday 10am-8pm. Admission to the museum is free, the only expense is parking (which you won’t have to worry about if you take the bus). The Getty does ask that you make a reservation on their website, although the staff are a bit inconsistent about checking to see if you actually have one.

The bus stops just outside the main entrance; from the stop you have to walk through the freeway underpass and then follow the signs upstairs to where the tram stop is. This entrance pavilion holds the main parking garage and has some restrooms and posted maps of the complex, plus a rather tranquil sculpture garden that a lot of visitors seem to overlook.

After you pass through security and a bag check, the staff will direct you to the platform where you board the automated tram that takes you up the hill. It’s basically identical to an airport people mover, although it’s unlikely any airport people mover gives you views this nice. The Sepulveda Pass opens up below you, dominated by the wide concrete ribbon of the 405.

It’s about a five minute ride to the top, where the tram deposits you into the tram plaza, a wide open plaza that marks the entrance to the main museum complex. Umbrellas are made available for visitors on days with inclement weather, be it rain or too much sun. A few large sculptures dominate the plaza, which otherwise is mostly featureless. From here, a prominent staircase leads you to the entrance hall, where you can start exploring the galleries.

The entrance hall is a spacious, circular room with a sun roof, with rainbow-tinted shafts of light passing slowly across the hall over the course of the day. A lot of the typical visitor functions are located here, like restrooms, the main gift shop, the meeting spot for tours, and the information booth. The info booth is impressive for the sheer number of languages that the printed maps are offered in.

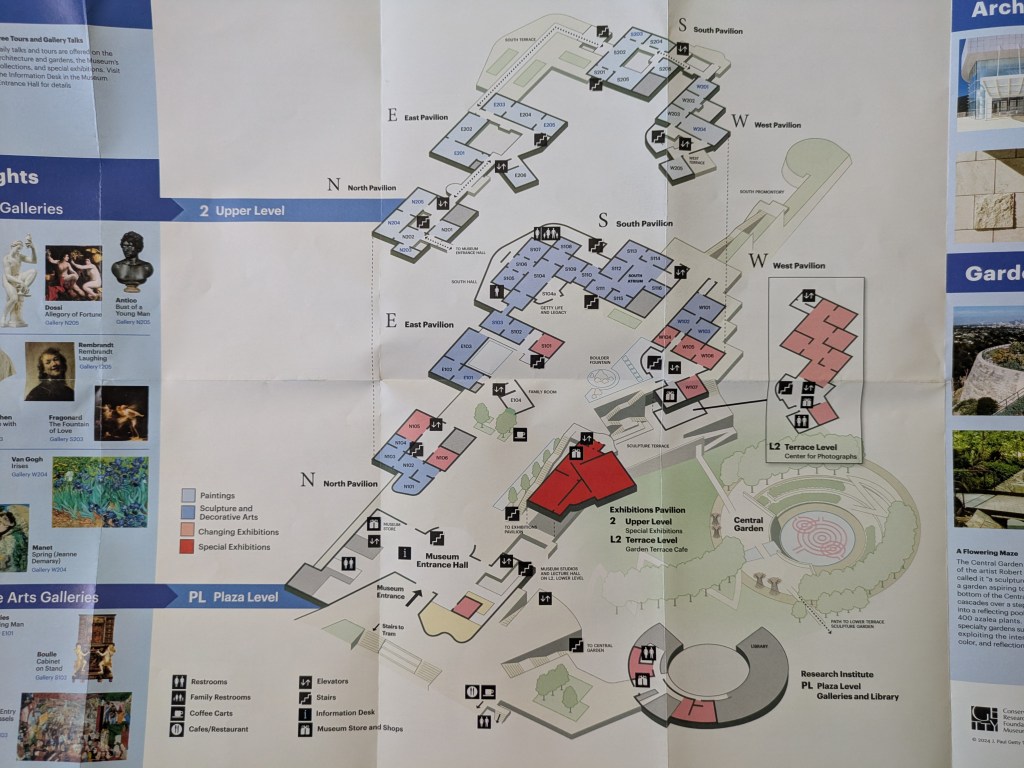

Now that we’ve actually entered the museum, let’s take a look at that map:

Despite the size of the complex and how imposing it seems, don’t let the map overwhelm you. The layout of the museum is actually surprisingly simple and easy to follow.

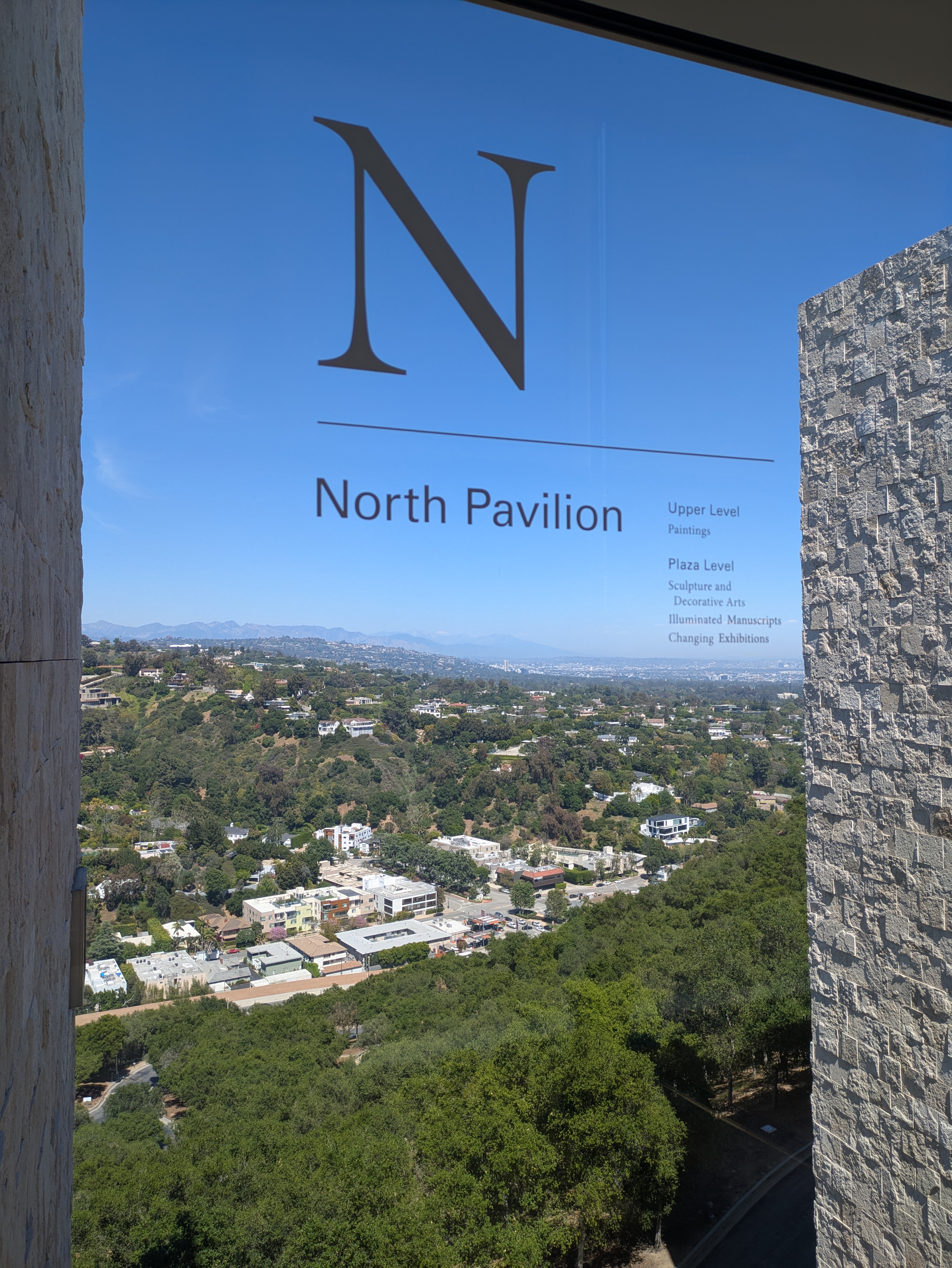

All of the main gallery pavilions surround a central courtyard, and all have two floors, with each building connected to the next on both floors. Bottom floor is for sculpture and decorative arts, top floor is for paintings. The collection is arranged chronologically, with the North Pavilion (the one attached to the entrance hall, on your left after you enter the hall) having the oldest stuff.

The only exceptions to this layout are the changing exhibitions. A exhibition pavilion sits on the right side of the courtyard after you pass through the entrance hall, and will have the most high-profile exhibitions, while West Pavilion has a third floor downstairs with photography exhibitions. But these are the only exceptions, all the permanent collection galleries follow the layout.

And if you need something more tactile than a paper map, the entrance hall and the courtyard have scale models with braille print!

The Galleries

We’ll start with the North Pavilion, which holds objects dating from the 1000s-1600s, with artwork from the Medieval and Renaissance periods. The oldest works here are the intricate illuminated manuscripts, the stuff of fanciful fairy tale books. Upstairs are some of the most striking works in the collection, from gilded panels from Medieval churches to Antico’s bronze Bust of a Young Man with its inlaid silver eyes. The work in this first building is deeply religious, reflecting the dominance of Christianity in Europe at this time.

The next building, the East Pavilion, contains art from the 1600s and 1700s, with a particular emphasis on Flemish, Dutch, and Italian art movements of the period. Here the work takes on more humanist and naturalistic qualities, with beautiful landscape paintings mixed in with the colossal portraiture. Among the highlights here are La Roldana’s strikingly realistic sculpture of Saint Ginés de la Jara, the lush reds of Anthony van Dyck’s massive portrait of Agostino Pallavicini, which sits right next to Bernini’s Bust of Pope Paul V, and several Rembrandts. Look up as you enter the first gallery on the second floor, where you’ll be greeted by Musical Group on a Balcony, a fun ceiling painting of a group of revelers partying above you.

The South Pavilion also covers art from the 1600s and 1700s, and while much of Europe is represented, the focus here is decidedly French. Here you’ll find one of the biggest highlights of the museum, the period rooms that recreate the interior design enjoyed by the French aristocracy prior to La Révolution, complete with elaborately paneled walls, intricately carved furniture, four-poster beds, chandeliers, and giant mirrors.

Another highlight of the first floor of the South Pavilion is the South Hall, a curving hallway on the corner of the building with wide windows overlooking the city. Inside the hall itself are elaborate works of silver and French porcelain.

Upstairs, half of the South Pavilion is given over to an outdoor terrace with a couple of sculptures, while the galleries have paintings from 16th and 17th century masters such as Goya and Thomas Gainsborough and an entire room devoted to romanticized paintings of Venice.

The last building of the permanent collection, the West Pavilion, has the newest objects in the collection, dating from 1800 onwards. Upstairs is where you’ll find the Getty’s collection of Impressionist paintings, including such recognizable names as Monet, Manet, Renoir, Cezanne, and Van Gogh. The works here are beautiful, and definitely the most exciting to see for visitors who have a more casual knowledge of art history.

Downstairs, the works are quite varied, with neoclassical sculptures, a solitary Giacometti statue in the entrance hall, and a couple of notable paintings, including James Ensor’s colorful Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 and one of the most beloved and humourous works in the collection, Joseph Ducreux’s Self-Portrait, Yawning, in which the artist portrays himself theatrically yawning.

The West Pavilion also holds a bunch of rotating exhibits in its downstairs galleries, with the first floor having a few galleries devoted to drawings, while a third floor further down (the “Terrace Level”) holds the Center for Photographs, with exhibitions showcasing photos drawn from the famous Getty Images archive.

Changing exhibitions are also held in two other buildings: the most high-profile ones are held on the second floor of the Exhibitions Pavilion, which has a long, prominent stairway outside leading up to the gallery entrance, with the bottom floor taken up by an open-air seating area for the cafe downstairs.

There is also one additional building on the complex that’s open to the public, and easy to miss since it’s separate from the main cluster of museum buildings surrounding the courtyard. From the top of the stairway that leads down to the tram station, walk towards the ocean, past the center’s main restaurant (itself a separate building) and through the stone archway to the Research Institute. This is the private research archive of the Getty, where visiting scholars work, but there is also a small gallery inside that hosts changing exhibitions. The exhibits here focus more on modern and contemporary themes, drawing from the objects held in the research archive. At the exit to the gallery to return to the lobby, you’ll walk across a suspended walkway that gives you a glimpse into the library below.

The Architecture

The buildings themselves are an attraction of the Getty. Arranged along an axis on the ridge of the hill, the buildings are a mixture of sleek, curving facades and imposing, blocky forms clad in stone. Many of the facades are covered in travertine, a porous limestone imported from Italy that gives the walls a rough texture, sometimes with fossils of leaves or shells embedded within.

Throughout the complex, buildings are arranged in such a way to maximize the views and create interesting vistas. There are plenty of hidden surprises that reward exploration and repeat visits. One such example is the enclosed passageway on the second floor between the North and East Pavilions, where a little alcove offers a cozy place to sit and enjoy the view.

The South Pavilion has more lovely views, taking advantage of its perch on the side facing the city. Downstairs, the South Hall has wide, curving windows rounding the corner of the building while upstairs an outdoor terrace offers a panoramic view from a small garden.

The architecture often feels fortress-like, and truthfully the Getty can be thought of as a massive art fortress, one employing the most advanced technology needed to secure the art. This comes into the public light every few years or so, when a brush fire licks the slopes somewhere in the vicinity of the museum. When this happens, the buildings’ ventilation systems are pressurized to prevent smoke from entering and damaging the art, while fire suppression techniques keep any danger far from the buildings themselves. And yet, despite the relative frequency of these events, cries of alarm ring out from the city every time flames are visible anywhere in sight from the Getty. Even if we don’t want to admit it, Angelenos are morbidly fascinated by the notion of the Getty’s destruction.

Those fire suppression techniques are visible, if subtly so, around the grounds of the museum. Not only are the imposing buildings themselves reinforced with fire-resistant materials, and not only is there an extensive irrigation system, but the surrounding landscape is kept clear of fuels and cultivated with drought-resistant plants, designed specifically to slow the spread of fire. You can see this for yourself at the very southern tip of the complex, where a narrow structure extends out along the ridge from South Pavilion. This is the South Promontory, which is planted with a cactus and succulent garden to take advantage of the full sun the slope receives, while providing the benefits of drought-tolerant landscaping. A stairway leads down past the garden to a small observation deck with uninterrupted views of the city.

The courtyard is very impressive and a focal point for visitors, with a trio of fountains amidst the crowds of people. Extending from the entrance hall along the Exhibitions Pavilion is a long narrow fountain with small arcs of water, filling the surrounding space with the pleasant sound of splashing water. In front of West Pavilion is a wide, circular fountain marked by a set of large granite boulders emerging from the water. And pressed up against East Pavilion tucked into a corner is a quiet pool of water that splashes softly, its slight ripples casting reflections on the travertine walls.

There are a lot of views which impress upon you the scale of the Getty Center, but none are more striking than looking out from beneath the Exhibitions Pavilion. Here the blocky mass of the second floor is suspended above the seating area for the cafe below, a huge structure held up by thin stone pillars, casting a shadow on the diners below.

Nearby, between the Exhibitions Pavilion and West Pavilion, a sculpture terrace (featuring works by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore) creates a gradual approach from the museum courtyard to the gardens below. And speaking of the gardens…

The Gardens

Laid out in a shallow ravine just below the buildings of the Getty Center, the Central Garden is a lush oasis of greenery that’s one of the highlights of a visit here, and certainly the most interesting attraction for visitors who aren’t as invested in the art. Designed by SoCal-based installation artist Robert Irwin, it was designed to be sculptural in form, itself a work of art.

From the museum, you can make your way down into the garden from the sculpture terrace or from a set of stairs leading down from the entrance plaza. Taking the latter approach, you’ll follow a zig-zagging path downhill, which passes through a shady grove of trees planted along a trickling stream that runs down the center of the ravine. Beneath the trees, the grove is full of beautiful plantings of flowers and succulents, grouped by color and texture. Boulders placed in the stream itself create different ambiences, with the sound of the water changing as you move downhill.

Emerging at the bottom of the path, the stream cascades down a stone wall into a pool at the center of the garden. Within the pool itself, a flowering maze of shrubs is planted in a very geometric pattern, the most “sculptural” element of the garden. From atop the stone wall, you can admire the water below or take a seat in the shade of the nearby flowering “trees,” a set of structures of steel rods supporting flowering vines.

The pool is surrounded by the specialty gardens, and these are the true highlights of the garden. From the south side of the pool, a narrow pathway loops along the sides of the pool past lush beds of gorgeous flowers and through wooden archways supporting flowering vines, all with the maze and the buildings of the Getty as an elegant backdrop. As you can imagine, this is the most popular spot with photographers, and that narrow pathway will get jam-packed with visitors negotiating their way around each other and trying to pose for pictures as traffic backs up behind them.

But don’t let the crowds dissuade you from entering, because otherwise you’ll miss out on the lush grandeur of the gardens that’s really best appreciated up-close. The flowers are arranged in beautiful displays of color, ranging from cooler tones on the western side to warmer ones on the east. And the flowers themselves vary in texture, from simple forms to spiky-headed crowns. And this is to say nothing of the smell, which is downright heavenly.

One last space remains to be explored, and it’s one that’s easy to miss if you don’t keep your eyes open. Heading up a path out of the Central Garden leading away from the museum will take you to the Lower Terrace Sculpture Garden, the fourth and final of the Getty Center’s outdoor sculpture gardens/terraces. This one has a handful of large, modern sculptures, arranged around a broad terrace with a view over the city. The most notable works here include a pair of Alexander Calders and Walking Flower by Cubist painter Fernand Léger. Just be sure to obey the many signs forbidding you from walking in the planters or on the grass.

At this point, you’re probably eager for a bite to eat, or maybe something to drink. There’s a coffee cart back in the museum courtyard, or perhaps you’d prefer to nurse a cocktail from the outdoor bar attached to the restaurant. Just be aware that you’ll be paying museum prices for anything here, and it’s a long ways back downhill to civilization. You are actually allowed to bring food with you (no alcoholic beverages) and enjoy a picnic out in the garden, just be sure to check your coolers or picnic baskets at the coat check in the entrance hall before you try to take them into the galleries.