In the 1870s, there was a growing push from Southern California’s elite for the establishment of a university that would serve the rapidly growing city of Los Angeles. Led by Judge Robert Widney, most of the money and land for the effort came from three prominent businessmen: Ozro Childs, a local merchant and banker; John Downey, a former governor of California and namesake of the suburb of Downey; and Isaias Hellman, Los Angeles’ first successful banker.

All four men were heavily invested in real estate and had played an outsized role in the transformation of Los Angeles from a predominantly Mexican settlement into a burgeoning American city. Their business enterprises were frequently intertwined. They were also involved in some significant L.A. transit history: Judge Widney had gotten the city’s first streetcar line up and running in 1874, and Hellman had also heavily invested in the city’s early streetcar lines. Years later, Hellman would co-found the famed Pacific Electric Railway after convincing railroad magnate Henry Huntington to invest in Los Angeles.

The University of Southern California opened its doors in 1880, on a campus situated at what was then the southern edge of town, set amidst fields and across the street from a fairground, no less. Soon enough, the city would grow around the campus, the fields giving way to houses and churches while the fairground was eventually converted into a park. Southern California’s first major university has since continuously shaped the area around it, with the university itself becoming widely recognized. Though not on the same level of prestige nationally as the Ivy League, USC still has a massive cultural influence, with its alumni filling the ranks of Los Angeles’ political and social elite. This has given USC a reputation as a rich kids’ school, an image only bolstered by the many bribery scandals the university has been embroiled in over the years. On the more positive side, USC looms large in the entertainment industry, with one of the most prestigious film schools and dramatic arts programs in the country.

USC’s campus has a lot for the visitor to enjoy, all within easy walking distance of a Metro Rail station. This guide will cover both the campus and the quiet neighborhood of University Park just to the north, while the popular attractions of Expo Park just south of campus are covered in that guide.

Important note: I wrote this guide in 2024, when the campus was very accessible and open to the public while school was in session, but now every pedestrian entrance is gated with an ID check and security staff who will ask you what your purpose on campus is. As such, it’s a lot less accessible to the public than when I wrote this. If you do indeed have business on campus, great, but you can also skip to the ‘University Park’ section for the part of this guide that covers off-campus attractions.

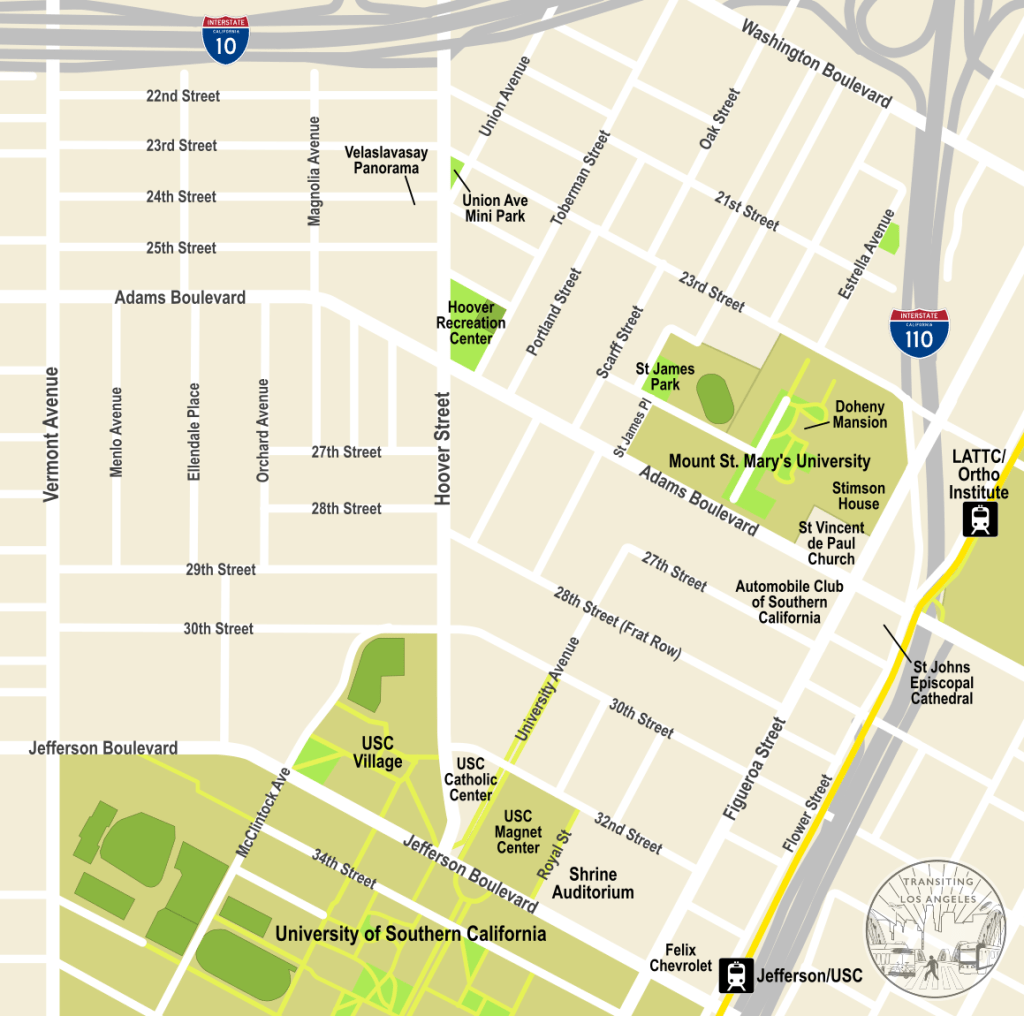

USC is easily accessed by transit, thanks in large part to the Metro E Line (formerly the Expo Line), which makes several stops in the neighborhood. Expo Park/USC station is the best one for accessing the USC campus, and the one we’ll be using as our starting point for this guide, as it is very conveniently located at the southern end of the main walkway through the heart of campus. However, there are also stops at Expo/Vermont, at the southwestern corner of campus; Jefferson/USC, across the street from the Galen Center arena on the eastern edge of campus; and LATTC/Ortho Institute, which is a bit more of a walk but can be handy for visiting the University Park neighborhood north of campus.

And then there are plenty of frequent Metro bus lines that serve USC. #2 starts along Figueroa past USC and takes Hoover north to Westlake and Echo Park before taking Sunset Blvd all the way to rival school UCLA. #81 runs along Figueroa on the east side of campus, while #204/Rapid #754 run along Vermont on the west. The DASH F shuttle loops around campus before taking Figueroa up to Downtown L.A. And lastly, the Metro J Line (formerly the Silver Line) is an express bus line along the 110 freeway, stopping at a freeway station at 37th Street/USC, a couple blocks from the southeastern corner of campus.

USC occupies a pristine and compact urban campus, situated between Exposition Blvd on the south, Jefferson Blvd on the north, Vermont Avenue on the west, and Figueroa on the east. The architecture has a very uniform red brick style, though this varies from older Italianate-style buildings to blockier, modernist buildings. Though overall very pleasant, the uniformity of the architecture means that there are only a handful of standout buildings. Fortunately, we’ll be starting off with one of the best.

Directly across the street from the USC/Expo Park station is the picturesque clock tower of Mudd Hall, one of the oldest buildings on campus and certainly one of its prettiest, with architecture inspired by Medieval monasteries. In front, at the base of the clock tower, is a scenic courtyard with a fountain and a covered walkway of candy cane arches, which makes for a very popular backdrop for graduation photos and LinkedIn profile pictures.

Mudd Hall houses the philosophy department, which is reflected by some of the hidden features on the façade, like stone figures and carvings that reference historic philosophers. But the real highlight is inside. Upstairs, you’ll find the Hoose Library of Philosophy (open Monday-Friday 9am-5pm), which is almost certainly the architectural highlight of the entire campus.

You’ll be in awe as soon as you step inside the library, with its arched columns reaching to the high ceiling. Between the stacks, tall windows allow sunlight to pour in, with tile mosaics depicting famous philosophers. At one end of the room is an array of beautiful stained glass windows, while at the other end is a brick fireplace with plush armchairs that would look right at home in a Harry Potter film (unsurprisingly, this room has indeed been used in a bunch of movies). Even the staircase leading up to the library is impressive, with its tile steps and intricately carved banister.

Next door, directly behind Mudd Hall, is the USC Fisher Museum of Art, which credits itself as the first museum in Los Angeles devoted exclusively to art. The museum is located within the art building, but it has a prominent entrance facing Exposition Boulevard; you just have to walk around the corner from Mudd Hall, where a small sculpture garden will greet you at the entrance to the museum.

For a college museum, the Fisher has a very prestigious art collection, however there is no permanent exhibition on display. Rather, the Fisher hosts changing exhibitions that tend to be very good. So be sure to check the website to see what is currently on display. When an exhibition is open, the museum’s hours are Tuesday-Saturday, 10am-5pm, with free admission.

Returning to Mudd Hall, you can start up Trousdale Parkway, the main walkway that leads you into the heart of campus. Right in the center at the start of the parkway is a statue of a shaggy dog dubbed George Tirebiter, a stray dog on campus so named because he apparently loved chasing cars and biting the tires. After being taken in by the students, he became a beloved mascot at USC football games in the 1940s and ’50s.

This stretch of the parkway is very manicured, planted with shade trees and beds of flowers in the school colors. Past the first couple sets of buildings, you’ll enter Hahn Plaza, the very heart of the campus, surrounded by some of its most prominent buildings: the student union and the campus center (with various student functions and a food court) to the southwest, the Bovard Administration Building to the northwest (also a bit of an architectural landmark), and the main library just across the public square to the east.

The plaza itself has two notable landmarks: a lovely fountain overlooked by a rather stunning, gleaming white statue of Traveler the Horse, USC’s animal mascot since the 1960s, who rides into football games with a trojan soldier on his back. The other landmark is a statue of Tommy Trojan, the university’s most popular mascot, in front of the Bovard Building, which serves as a common meeting spot as well as the target of various school pranks and hijinks.

Continuing across the square, Doheny Library sits directly across facing the Bovard Building. Security will ask you to present a photo ID when you enter, but it’s worthwhile to see the architecture inside. A small exhibit hall called the Treasure Room is located down the hallway to your right, which hosts changing displays related to Southern California history and has some interesting murals to admire.

Doheny Library houses many of the university’s special collection libraries, some of which have small sections of the building devoted to them, with displays for visitors to enjoy and lots of fascinating material available for access. The most notable of these is the Cinematic Arts Library down in the bottom floor, the reading room of which is filled with remarkable artifacts. The walls are lined with classic movie posters, and walking through you’ll pass display cases of artifacts from old Hollywood, including an entire set of objects related to Cecil B. DeMille. It’s very much worth a look if you have even a casual interest in film, and for the more invested you can arrange with the librarians to explore their collection.

Doheny Library also serves as the focal point of the annual L.A. Times Festival of Books, which takes place annually every April and is the premier literary event in Los Angeles, if not all of California. The festival hosts an absolutely stunning lineup of authors, publishers, and booksellers covering every genre and aspect of the written word. Whatever weekend it’s happening, you’ll find the quads surrounding the library to be jam-packed with vendors and performances, with every auditorium on campus given over to readings and panels. It’s all free to the public, and if you’re willing to scan through the incredibly dense schedule and lists of participating authors, you’re sure to find something that’ll catch your interest.

Directly behind the Doheny Library is a small rose garden adjacent to a wooden, white-painted house that stands out for looking nothing at all like USC’s normal palette of red brick and concrete. This is the Widney Alumni House, dedicated in 1880 and not just the oldest building on campus, but the oldest existing university building in all of Southern California. This was USC’s first building, and it has been moved several times to accommodate the expansion of the campus. Today it houses the alumni association, and has an elaborate plaque out front explaining the history of the building.

Going north around the back of Doheny Library leads you into McCarthy Quad, a large lawn that plays host to major campus events as well as the weekly Trojan Farmers Market, which takes place every Wednesday from 11am-3pm during the fall and spring semesters. On the west side of the quad is the Center for International and Public Affairs, a fairly iconic building on campus that is immediately recognizable by its lofty tower topped with a globe. Built in 1964, the building was designed by Edward Durell Stone, a prolific modernist architect who designed many notable buildings, including MoMA in New York City, the JFK Performing Arts Center in Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Embassy in India. This is probably his most recognizable building in L.A., although he also designed university buildings for Caltech and in Claremont.

The building has been renamed in honor of Joseph Medicine Crow, and you’ll find a tribute to him at the base of the tower. Medicine Crow was a famed Native American historian and author, noted for his heroics in World War II as well as his insights into Native American culture. He earned a master’s degree from USC in anthropology, becoming the first member of the Crow tribe to receive a master’s degree and eventually establishing himself as one of the university’s most renowned alumni.

Continuing west back across Trousdale Parkway, you’ll enter a shady green space named Founders Park, where you’ll likely encounter some of the campus’ many fearless and very persistent squirrels, who will come right up to you and expect food. Just past the park on the right-hand side are the Bing and Cinema Theaters, which regularly showcase student performing arts shows or films. The Cinema Theater, in a nod to USC’s rich connections to the entertainment industry, has some tributes to famous filmmakers on the back side of the building (facing Founder Park) and a tribute room to Frank Sinatra in the entrance lobby on the front, across from Bing Theater.

Past the theaters is the Heritage Hall, which serves as the gateway to the athletics center and sports fields on the west side of campus. The building itself holds a little museum celebrating the USC athletics division, with a “Hall of Champions” full of trophies and awards in the lobby and more artifacts in an adjacent gallery. Even for non-sports fans, there’s some fun stuff to look at in here, like an old Trojan mascot costume and a room for a big trophy cup that gets swapped between the winner of last year’s USC-UCLA rivalry.

Just to north of Heritage Hall is one of the crown jewels of the university, the School of Cinematic Arts. It’s hard to overstate the level of influence this school has had on Hollywood; this is one of the oldest and most prestigious film schools in the country, with an alumni list to match. The two wings of the main building are named for Stephen Spielberg (who did not attend USC; he was rejected by the film school and attended Cal State Long Beach instead, which he dropped out of to intern at Universal Studios) and arguably USC’s most famous alum: George Lucas. Separating the two wings is a lovely Mediterranean style courtyard with a bronze statue of silent film legend and “King of Hollywood” Douglas Fairbanks, who had a hand in the development of the school.

The school is littered with tributes to actors, directors, and screenwriters with USC connections. There’s film posters and sponsor plaques with familiar names in various hallways. In the atrium near the on-site Coffee Bean is a statue of Bart Simpson, in honor of voice actress Nancy Cartwright. And in the Lucas wing, there’s a gallery with changing exhibitions focused on specific filmmakers.

And then there’s the men’s restroom in the Lucas wing, where every single urinal and toilet stall has been sponsored by a film producer or writer, with accompanying signed film posters of the movies they worked on. Fittingly, the movies highlighted here are mostly raunchy comedies of the 2000s and 2010s, starring actors like Paul Rudd and Adam Sandler.

Returning to Trousdale Parkway and continuing north, you’ll cross a small street before you approach the gateway onto Jefferson Blvd, the northern edge of campus. But before you reach it, look on your right for a small brick building, the University Club, a private clubhouse for faculty and staff to schmooze with VIPs. The clubhouse is only open to members, but there is a lovely Japanese Garden hidden around the corner on the side facing Jefferson that’s open to the public and is a nice spot for a tranquil moment.

University Park

Across Jefferson Blvd, you can’t miss the audacious architecture of Shrine Auditorium, a true landmark and a particularly noteworthy example of Moorish Revival architecture. Built in 1926, it serves as both an event venue and a local headquarters for the Shriners, a Masonic society most well-known for their network of children’s hospitals. The auditorium has hosted numerous awards ceremonies and major concerts over the years, and is a sight to behold with its gleaming spires and elaborate stained windows.

Returning to the northern gateway of campus and crossing the scramble crosswalk at Jefferson and Hoover, you’ll enter USC Village, a massive housing and retail complex built to serve the student population. When classes are out, this becomes arguably the center of activity on campus, with swarms of students running errands, grabbing something to eat, or just relaxing in the massive Italianate piazza adorned with a statue of Hecuba, the mythical queen of Troy. There are plenty of great places to eat here, or you can grab a coffee from the immensely popular location of Cafe Dulce.

Across the street from USC Village, at the corner of Hoover and 32nd Street, is the USC Catholic Center, which boasts a lovely church. Inside is a frighteningly imposing sculpture of the crucifixion suspended over the altar and some impressive stained glass windows, which are worth peeking inside to take a look. However, the main attraction here is the center’s own popular coffee shop, Ministry of Coffee, a quieter and still delicious alternative to Cafe Dulce.

Continuing up Hoover, you’ll enter University Park, a historic neighborhood that has grown alongside the USC campus since its inception. Given that it was laid out over a hundred years ago, the architecture is a mix of styles, with a lot of Victorian houses that have been converted into duplexes, mixed in with grand churches and modern apartment buildings. Most of the residential streets are quiet and pleasant to walk down (with the notable exception of 28th Street east of Hoover, which is infamous as Frat Row and frankly better skipped), but even just walking up Hoover you’ll be treated to plenty of fine architecture. At Hoover and Adams, you can’t miss the former Second Church of Christ, Scientist building, a towering Classical Revival structure with a massive copper dome which looms over the surrounding blocks.

University Park’s best attraction is just a bit further up Hoover. Just around the corner to the west on 24th Street, in the eye-catching former Union Theater, is the delightfully unique Velaslavasay Panorama, which feels in many ways like a spiritual sister to the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Culver City.

Painted panoramas were a fairly popular form of entertainment in the 19th century, and in some regards can be thought of as a precursor to cinema. The concept is simple, even if the execution is elaborate: the viewer enters the theater via a staircase, which leads to a platform surrounded on all sides by a realistic painting, assembled so as to mimic a panoramic view. This 360-degree painting, enhanced with props in the foreground, dynamic lighting, and sometimes even audio, immerses the viewer into the setting.

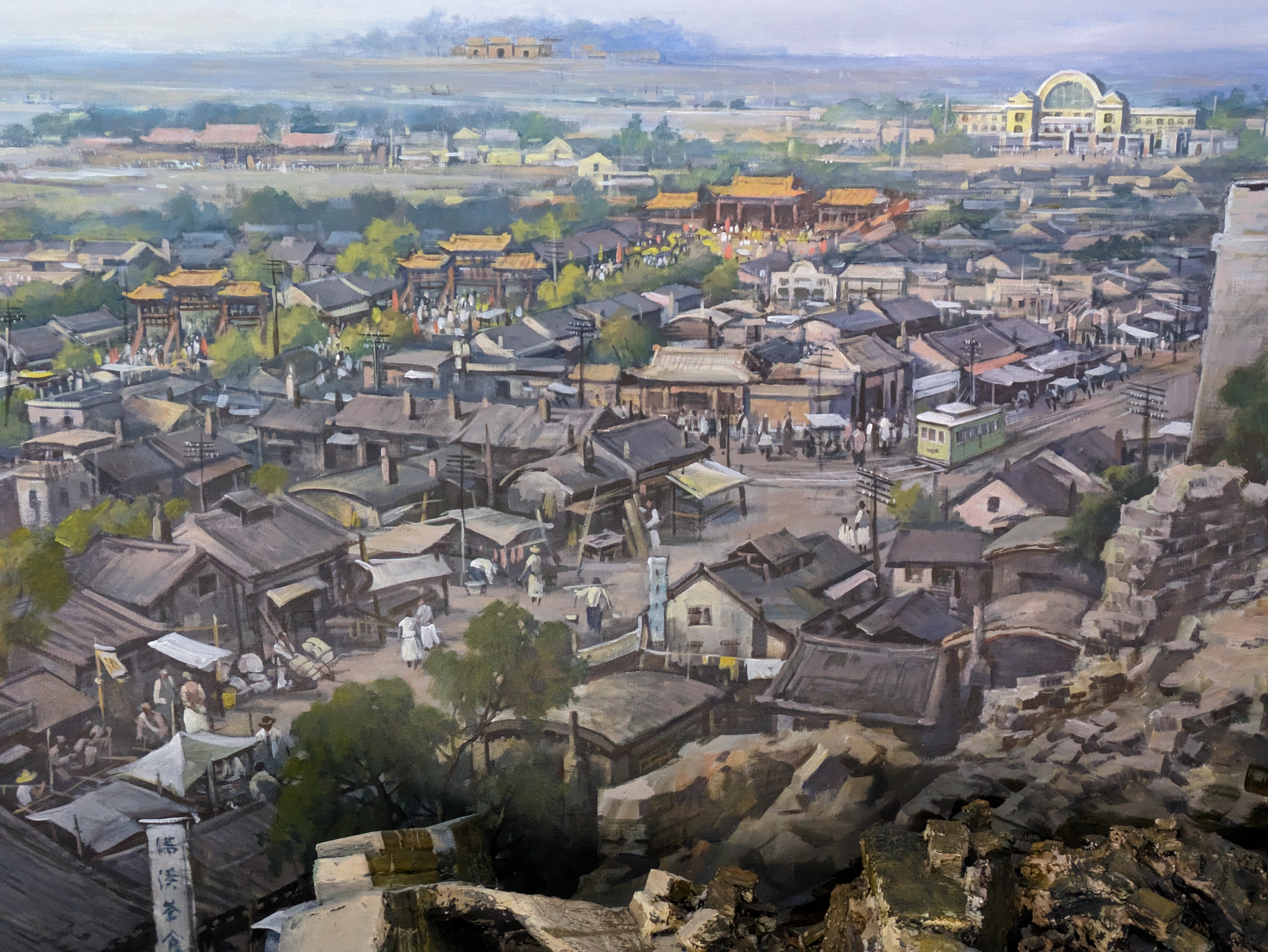

Only a handful of historic panoramas survive to this day, though the artform is kept alive through the occasional modern iteration. That’s what has been accomplished here, and the effect is breathtaking. After you’ve entered the lobby and checked in, you’ll proceed down a set of dark hallways and ascend a spiral staircase to view the museum’s current masterpiece, the Shengjing Panorama, which depicts the city of Shenyang around 1920.

The details are incredible and warrant lengthy viewing. On one side is the old walled city, bustling with urban life, while on the other side the new city stretches out along wide boulevards to a grand railroad station, with distant columns of smoke from approaching steam trains. As you’re viewing all of this, sounds from the city below fill the theater: vendors hawking their wares, horse carts rattling through the streets, birdsong, train whistles in the distance. And as you keep watching, the light begins to change, circulating between day and night as lush purples and soft pinks engulf the sky at dusk.

The panorama is the highlight here, but there are other fascinating exhibits as well. While the exhibits here do rotate (so any of this is subject to change), they do so infrequently enough to feel like permanent exhibits. Just off the lobby down a separate hallway is a recreation of an Arctic trading post from the turn of the century, with heavy pelts draped over chairs and artifacts of Arctic expeditions past, and even a miniature diorama of the tundra viewed through a window. Down the hallway leading to the panorama are a couple of models of historic L.A. buildings, including one of its former train stations. And further down in the old theater, where a small stage still sits, is a collection of models related to previous subjects of the musuem, including a model of the original Velaslavasay Panorama location in a former Chinese restaurant in Hollywood.

The last feature of the museum is a lush and tranquil garden in the very back, entered through the theater. There’s plenty of places to sit, including a lovely little pagoda, as well as serene fountains and scattered bits of poetry.

The panorama is only open to visitors on Fridays and Saturdays (and the very occasional Sunday) from 11am-4pm, with admission being $7 per person. You can check the website ahead of time to see available times and book appointments.

Continuing our walk around University Park, there’s a nice little public square across Hoover from the Velaslavasay Panorama, situated in the triangle formed by Hoover, 23rd Street, and Union Avenue. This little park is surrounded by a collection of storefronts with some nice coffee shops and restaurants. From here, we’ll continue east to the neighborhood’s other notable park, St. James Park, which sits on St. James Place halfway between Adams Blvd and 23rd Street, a few blocks east of Hoover. Though it’s a fairly plain lawn with some weathered planters today, at one point St. James was one of the most desirable neighborhoods in the city, a wealthy enclave at the turn of the century filled with Victorian houses, many of which still survive.

St. James Park also marks the entrance into the campus of Mount Saint Mary’s University, with the main gate just a block east of the park. This Catholic university encompasses the entirety of Chester Place, one of the city’s first gated communities and, in the 1900s, perhaps its most exclusive addresses. The campus is centered around the Doheny Mansion, the Gothic residence of the city’s first oil tycoon, with lush landscaping and other historic buildings, including an odd stone tower hiding just south of the mansion.

As far as I could tell, the St. James Park entrance is the only one that’s open, so exiting the campus requires going out the way you came in. From here you can loop down to Adams Boulevard and continue east to Figueroa, where the intersection is surrounded by stunning buildings. First is the beautiful St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church, built in the 1920s in a spectacular Spanish baroque style with an elaborate tower soaring over the street. Directly north of this on Figueroa is the Stimson House, perhaps better known as the “Red Castle” for its medieval-style architecture and red stone facade. And on the southeast corner of Adams and Figueroa (and behind a gas station) is St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral, which is quite stunning inside.

On the southwest corner of Adams and Figueroa is the headquarters of the Automobile Club of Southern California, the SoCal affiliate of AAA. Besides being a pretty building, it reflects the prestige of the organization back in the day; today, AAA is known mainly as an insurance company, but when this building was built in the 1920s, the Auto Club was a political force to be reckoned with. It was a powerful lobbying group pushing for the improvement of roads, adoption of standardized traffic laws, and the general advancement of car culture, producing road maps, launching a tow service, manufacturing road signs, and adopting a business incentive program (the once much-heralded “AAA discount”). In short, it played a big role in creating the car-centric California we know today.

Returning to the campus via Figueroa, there’s one more neighborhood landmark to take in. At the intersection of Jefferson and Figueroa, across the street from the Galen Center basketball arena, is one of L.A.’s most iconic signs. Local car dealer Winslow B. Felix opened Felix Chevrolet in 1921, just two years after the introduction of Felix the Cat, which quickly became one of the most popular animated characters in history. Felix (the car dealer) became friends with Felix the Cat’s creator and was granted the right to use licensed images of the character to promote his dealership. In 1957, a giant three-sided neon sign was added to make the business visible from the newly-constructed 110 freeway. A massive parking garage has since been added to the back of the dealership, blocking the view of the sign from the freeway, but the sign still towers over Figueroa and remains an iconic symbol of the city’s car culture to this day.

From here, the Jefferson/USC station on the E Line is just a block east, so you can quickly return to the train there, or continue down Figueroa and reenter the USC campus if you want to return to the start.